614 Magazine published a feature article this month about my return to Columbus and the Every Wednesday Concert Series I started at Dick’s Den. I’d like to express my thanks to the writer, Mark Lucas, for doing a great job with some very sensitive issues. In this post I’ve included the article along with some corrections and additions.

Virtuoso, ex-con, Columbus’ prodigal son

By Mark J. Lucas

Christian Howes’ violin catapulted him to youthful success, provided him solace in the most miserable of conditions, and brought him into the close company of one of the most famous musicians in America. Now he is offering his talent to Columbus, once again.

At age sixteen, Christian Howes was on his way to early fame, one of the youngest professional musicians in the country, (I’m not sure what he means by “one of the youngest professional musicians in the country”, although it may have been a reference to the fact that at age 18 I was hired on as a full-time member of Pro Musica, Columbus’ s professional chamber orchestra) a prodigy playing violin with the Columbus Symphony Orchestra (As a result of winning the CSO young musician’s competition, I peformed the Mendelsohnn Violin Concerto in E minor, first movmt, with the CSO when I was 16; The concert was given at Fort Hayes Auditorium). A few years later, he was serving out a four-year prison sentence for trafficking LSD.

And only a few years after his release, he was playing alongside Les Paul at Carnegie Hall. (This isn’t exactly true. I did perform with Les Paul for over 10 years and I did perform at Carnegie Hall, but I never performed with Les at Carnegie Hall).

While America teems with the poetry of tribulation, sin, and redemption, Howes piloted his saga deliberately, not only recovering from failures others would have found crippling, but channeling them into powerful success . . . and then bringing it all back to his community.

To look at Christian Howes, you wouldn’t assume that he was a jazz violinist, even if you knew there was such a thing as jazz violin. He’s got large, meaty hands, with thick fingers that look like they’d be more adept at crushing the instrument than playing it.

Raised by musical parents on the Suzuki method of violin, a rigorous program that emphasizes music as a language (and thus best learned early), Howes has been playing violin since he was five years old under the tutelage of Virginia Christopherson at the Capital University Conservatory of Music, learning the context and the rules that govern music. Later, bending and even breaking those rules would make him a trailblazer.

“[I] stayed involved with the classical stuff,” said Howes, “but also started playing in rock bands in high school – bass and guitar and stuff, just because that was the hip thing to do.” (What I meant was that my friends were more interested in Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix than Brahms and Bartok, and the girls seemed more attracted to guitar players…)

Upon graduating high school a year early, OSU offered the budding genius (ok, sorry, but the term “genius” is overused, and it definitely does not apply to me. I’m thankful for having an early start at the discipline of violin under the watch of great teachers and supportive parents, and luckily, I took to it in high school thanks in large part to summer stays at Chataqua’s performing arts camp, where I was inspired by like-minded peers to really take music seriously-that’s when I really took off and started to distinguish myself. I’m a firm believer in Suzuki’s saying that “every child is endowed , more or less equally, with talent (rough translation!) a deal he couldn’t refuse.

“I was kind of a big fish in a small pond, as far as the music school was concerned,” he said. “I was in the honors program, the honors dorm and all that stuff.” (What’s not printed, but implied, is that while I was excelling in the context of academic placement, a professional gig, and my status within the music school hierarchy, I didn’t feel that I had found my “place” socially, i.e. I didn’t know where I fit in. This was at the trail end of my high school years which had been characterized at times by self-destructive and rebellious behavior. If there’s anything good that’s come out of this, it’s that I feel I can identify with my teenage and college-aged students. Not only do I relate to them, but I get the sense that they take me seriously when I talk to them about the importance of keeping their heads on straight, avoiding the pitfalls of bad habits and distractions such as drugs and alcohol, and the fact that there’s a direct line between the discipline they establish now and where they will end up in their lives and careers 10-20 years from now. Through my annual Creative Strings Workshop, my travels as a clinician, and my work at the Berklee College of Music as a private violin teacher, I really enjoy the relationships I have with so many young players whom I feel have put their trust in me as a mentor. I definitely realize that the choices I made were destructive to myself, my family, and my community, and hopefully I’ve been able to make a difference in my students’ choices as a result of the lessons I’ve learned . Some may feel that may background disqualifies me to be a teacher, but based on the strength of the relationships I have with my students, I would argue that the opposite is true.)

Young talent often a bedfellow of isolation makes. Still in his teens, and without many others his age to relate to in school, Howes sought companionship with twenty-something musicians outside the classroom. This brought about a change in direction that would later shape him for the rest of his life.

“I kind of got into that quasi-hippie scene a little bit,” explained Howes. “It was a way to find my place, to make me feel like I was a part of something. I was just kind of a pothead that passed around little bags, and then I got caught up in this stake – it was an LSD thing.”

Early in the 1990s, Howes ended up selling 15 sheets of acid (roughly $15,000 worth by today’s standards) (Whoa, hold up- drop a zero! This is very misleading. A sheet of acid, i.e., LSD, is comprised of about 100 tiny doses, each of which might retail separately for $3-5 in 1992. Sold by the sheet, the most one could take in would have been $150-200. Sold in bulk, the going rate for 15 sheets would have been about $100 per sheet, or $1,500. This is an important fact to consider when comparing sentencing guidelines for drug trafficking violations, because many people have argued that the sentencing guidelines for LSD are disproportionately harsh, if one uses the retail cost, and therefore economic impact, of the drugs as a measure. In other words, the “superbulk” or “drug kingpin” labels were supposedly applied to suppliers of “huge” quantities of drugs, presumably in part to account for the economic motivations and consequences of these illegal deals. But the economic comparisons did not add up when you compare the standard of “superbulk” for different drugs, for example, twenty lbs of marijuana (worth maybe $20,000), a kilogram of cocaine (worth perhaps $20,000), vs one sheet of LSD (worth $100). ) to an undercover cop and was arrested.

Due to the stiff penalties conferred on acid convictions, he found himself facing a sentence of 15 years to life, but because he pled guilty, he was given a reduced sentence, which he began at the state penitentiary in Chillicothe. Only twenty years old at the time, Howes wouldn’t again taste freedom until the age of 24 – but while in prison, he found music in the most unlikely places. (To be clear, I committed the crime at age 18, was indicted at 19, and sentenced at age 20.)

“When you’re in there, you’ll see that there’s music that happens in prison,” said Howes. “When you walk around a prison yard, you’ll have guys beating on picnic tables, doing rap and hip hop, and you’ll have some guy down the way strumming on a guitar and singing some classic rock tune, and you’ll have these gospel singers . . . you’ll have all the different factions and cultural groups, different generations, people from the city, people from the country, all gathering into different musical entities, but then you’ll have a lot of cross-pollination within that, too.”

Howes’ musical knowledge became an asset to him on the inside. Ordinarily, different factions within a prison would force new prisoners to choose one faction over the others, but because Howes possessed a skill that many inmates realized might benefit them on the outside he “was given a pass,” and found himself tutoring them in formal musical training.(The teaching I did was, more often than not, informal, although I did have some private students who would meet me every day in the yard, weather permitting. Some guys were overt about asking for lessons and others were less comfortable admitting that they wanted to learn from me. What do you expect? Would you think a 50-yr-old convict doing a life bit for murder would ask a 20 yr-old college kid outright for “lessons”? It was often more subtle than this. And more importantly, I learned from these guys. I learned about manhood, culture, life perspective…. I learned that my life had been relatively easy compared to what these guys had been through. I learned that soul expressed through music was a powerful thing that couldn’t necessarily be taught. I learned a lot from the largely “uneducated” men who grew up more often than not poor in group homes, juvey joints, foster homes, and what not…)

In an odd way, his stay would benefit him later as he began life over, restarting his career with a grassroots push – from the ground up.

“Being in jail, I realized that music is just an organic human thing that happens,” said Howes. “It’s not something that’s tied to press releases and record deals. Out here, we tend to think that being a musician requires you to make opportunities to play. ‘Who’s gonna hire me to play music?’ . . . In prison, you don’t think about that. You just play, because you have to,” he said. “That’s part of the humanity that comes into this very de-humanized environment. That was part of the reason that when I got out I wasn’t fettered by these ideas.(What I meant was that, when I was released from prison I didn’t have any pretense that my music career should be dependent on some kind of commercial infrastructure! In the joint I would play out on the prison yard, and I figured it should be the same in the free world- I would play anywhere I could play without overthinking it. So many artists get hung up on getting gigs. Just start by going out and playing somewhere. Keep doing it and things will come together.) I’d been to the lowest points that I could be, and there was no shame in my game. I just wanted to go out and do my thing.”

After being released, Howes went from place to place – from restaurants to small venues and clubs, introducing himself to the manager and offering to play for free for half an hour, then negotiating payment for more shows if they liked what they heard. He had a unique product to sell, as jazz is a genre of music not ordinarily associated with violin.

“You don’t think of violin being in rock music, jazz music,” explained Howes. “It’s an open field, which has its pros and cons, but I look at it as being an advantage. When I started doing it in Columbus, even 13 years ago, when I was 24, there was probably no one else in the state doing what I was doing. Maybe one guy in every state, or something. I felt like, ‘Why shouldn’t I be able to rock out on the violin?'” he said. “There’s no physical reason, there’s no scientific reason. The only reason is because of this culture of education. Violin players learn from a very early age in this very strict environment, which is all in its own enclave [that’s] separated from the rest of the world, and it’s all about the western-European canon of knowledge. This is part of the advent of multi-culturalism and globalization, really.” (In other words, the classical music education world is largely “white”. The teachers within each generation continue to be limited to their knowledge of “white”, i.e. European, forms of music. This is the only reason why string players typically don’t understand “swing”, “blues” and/or other elements of “black” (African American) music. When I was in prison it became very important to me to try to understand and incorporate elements of “blackness” in music, and learn to express them on the violin. I see this as an important responsibility if part of my role as an artist is to make a social statement that goes beyond melodies and rhythms. In prison I came to believe that we should all respect different traditions and different people. We should respect different ideas, world views, paradigms. I learned that a 35 yr-old crackhead doing his 4th bit in prison had important lessons to teach me, just as important as my philosophy teachers. Most of us don’t want to admit that we live in a racist, classist, sexist, homophobic world. Not saying that I’m somehow above all this, but rather that we should all acknowledge the extent to which we are a part of this systemic dysfunction, and by doing so, we can do small things to change it and ourselves. Part of my mission as an artist became to pass on the lessons I had learned. I feel that by playing “jazz” on the violin, it is in part a symbol of this need for us to leave our enclaves, go out into the world and embrace the ideas of those different than ourselves. By embracing not only the background that i come from, but also the newness of others from a different background, I believe it gives more depth and meaning to my music. It also makes a statement to others when they see a band which is either homogenous or mixed. Musicians reading this will know what I mean, whether they’re comfortable with it or not. More often than not I see musicians self-segregating into all-white bands or all-black bands. How can artists lead society without taking the necessary first step of embracing others “different” from themselves and making music together.)

Howes’s piecemeal self-marketing eventually led to him doing shows in other cities.

“I would go to Cincinnati and sit in on jam sessions, or I would drive up to Toledo for $75 on a Tuesday night, and play with some band up there. I would just do anything I could to try and book gigs outside of town. Then I started booking tours all the way up through Minneapolis and Iowa and Chicago, through Wisconsin . . . I would take different bands with me. I didn’t make any money.”

In his late 20s, it became clear to Howes that he didn’t have to run all over the country trying to get into the business. He could get acts to come to him and play locally at Dick’s Den on North High Street, just a stone’s throw away from where he grew up. He began tapping big name acts to come to Columbus, so that he could establish relationships that would get him work. His success aligned him with several prominent artists in New York. (This is what I’m back at now and really excited about again! I’m looking forward to bringing great talent to Columbus for my Wednesday Night Series at Dick’s Den. We’ve got a a Singer Songwriter show planned for Jan 20, 2010 featuring national artist, Stephanie Nilles, also an Alumni of my annual Creative Strings Workshop and Festival. I will be bringing many special artists into Columbus from time to time.)

“People started asking me to come to New York and do things, play on records, so I moved to New York,” recalled Howes. “I started making a lot of great relationships, probably most notably with Les Paul, and I played with him for the last eight years on his Monday gig at The Iridium.”

“He was a great friend, and a great mentor,” he said, of the famous guitarist and designer of the Gibson Les Paul electric guitar. “I got to know him very well. I got to play with him all the time. I played with a lot of great people in New York that were in different scenes: classical players, straight-ahead jazz players, Latin players. I really struggled in that scene, but eventually built a name for myself [there].”

(The list is long, but some of these people include: D.D. Jackson, Akua Dixon, Steve Turre, Frank Vignola, Joel Harrison, Mulgrew Miller, Donny McCaslin, David Binney, Dan Weiss, Gary Versace, Rez Abbasi, Adam Rogers, Bill Evans, Victor Bailey, Joel Rosenblatt, Spyro Gyra, Alain Mallet, Richard Bona, Jason Lindner, Dana Leong, Jack Dejohnette, James Carter, Dafnis Prieto, Sam Bardfeld, Rob Thomas, Dave Eggar, Nicki Parrott, John Coliani, Bucky Pizzarelli, Joel Newton, Oli Rockberger, Janek Gwizdala, Randy Brecker, Christian McBride, Paquito D’Rivera, Ada Rovatti, and many others…)

Eventually, the call of home reached Howes, whose daughter Camille lives in Columbus. Though he maintains an apartment in New York, he wanted to be closer to her. She studies under Virginia Christopherson at Capital, like her father before her, and she and Howes have played at ComFest together for the last six years.

“As I started working with my daughter, I realized that I really like teaching, and I’m really good at it,” said Howes. “So I started a camp called the Creative Strings Workshop out of Columbus, and it’s going to be in its sixth year, this year. The idea was that string players all around the world – adults – could come here and study with me and use my stomping ground, Columbus, as a scene to be inspired, so they’d learn where I learned: in the streets, in the clubs, in the theaters, in parks, playing for real people in a real community.”

The Creative Strings Workshop doubles as the Creative Strings Festival, in which Howes’ musicians (usually about 60 or so) play 25 concerts in five days. During the day, they workshop at Otterbein University, and every night they play at Dick’s Den. This year, it will take place between June 28th and July 4th. Though Howes is still in the market for new venues, past venues have included a variety of places, including Goodale Park, various restaurants, the North Market, and suburban stages around town. There’s even an education program for the kids, where they can observe the group.

“It’s wind powered,” explained Howes, “because [the musicians] need the experience of playing for people in new creative ways, and the city needs good talent.”

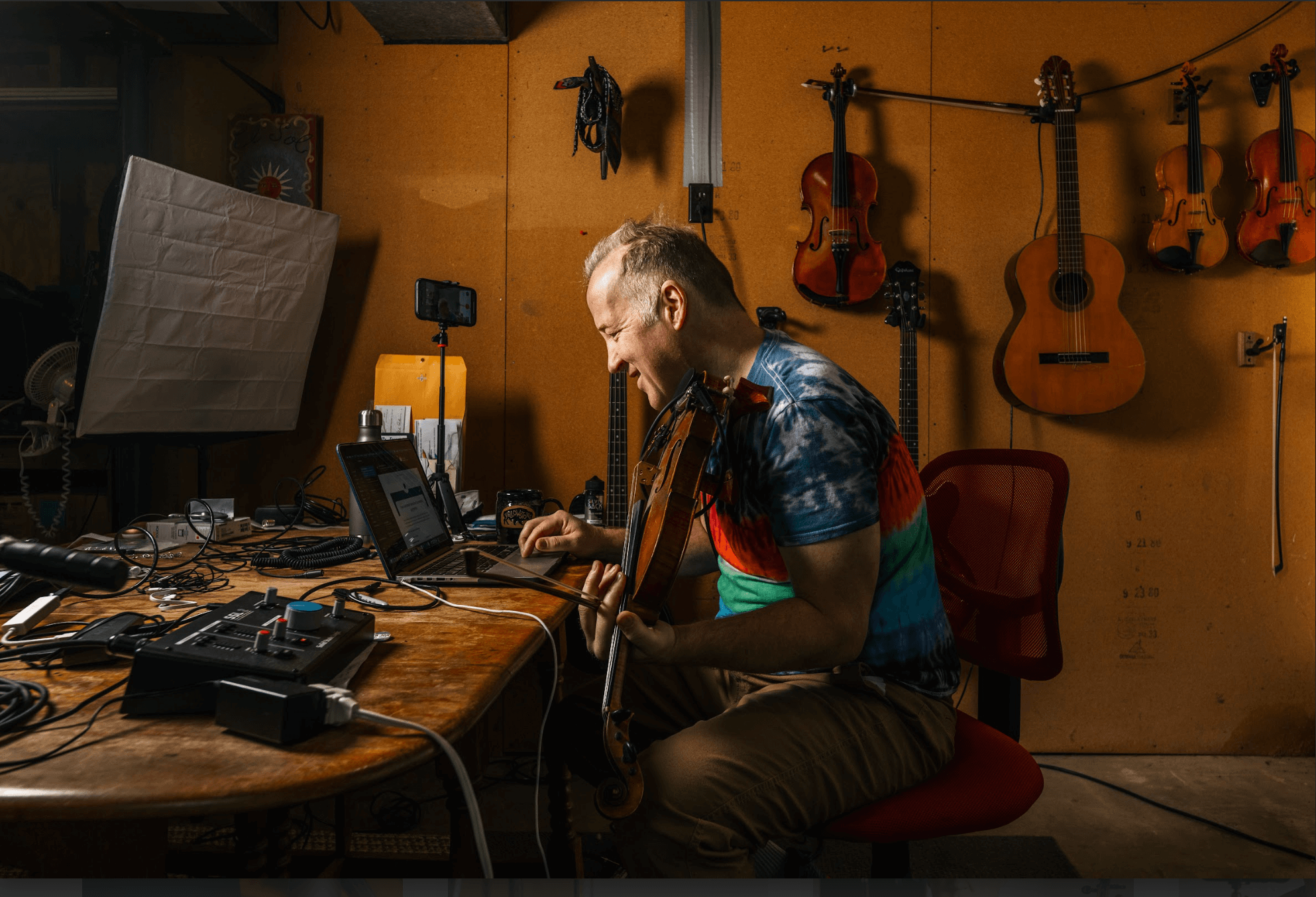

In addition to the Creative Strings Festival, Howes now hosts a show at Dick’s Den, where he got his start in jazz violin, every Wednesday.

“When I was thinking about setting up a base in Columbus again, I thought ‘Why not do Wednesdays at Dick’s Den,” said Howes. “I’ll be [there] most Wednesdays, but when I’m traveling, I’ll set up other special shows here, so that you know every Wednesday there’ll be someone special.”

It’s been quite the interesting journey for Howes, from the lowest lows to the highest highs, but fortunately for Columbus, he’s brought his wellspring of knowledge back to our neck of the woods. Jazz violin still isn’t very well known, but with trailblazers like Howes at the helm, it will assuredly find a niche in Columbus, and perhaps inspire another youngster, the way he was inspired. (Don’t get hung up by the word “jazz”. We’re performing original music that’s passionate, spontaneous, fun, and rich!)

See Christian Howes perform his stunning jazz violin at Dick’s Den (2417 N High St.) every Wednesday night. (Seriously, what else do you have to do?!)